Dad is the tough one; when he comes home, the two kids know there will be a “blow out” if he finds out about their behavior. He functions as the Persecutor, letting off his steam at Mom and the kids. But Mom is the Rescuer, jumping in to tell Dad he’s being too hard. And the kids know they won’t ultimately face consequences, because their parents will fight each other, both becoming a Victim and burned up that they are not respected by anyone in their household.

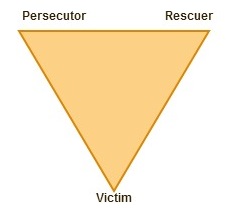

The Drama Triangle (founded by Dr. Steven Karpman, 1968)[1] brilliantly describes certain scripts found in relationships marked by dysfunction. These are generally unconscious “game plans” that take shape early in childhood. Here’s what the 3 roles look like:

Persecutor:

- Statements: “Get your act together!” “You are an embarrassment to this family.” “I am the one who has to whip people into shape- no one else will do it!”

- Behaviors: Yelling. Silent-treatment. Verbal put-downs. Blaming. Aggression.

- Internally: Driven by shame, anger is a cover for other avoided emotions. Though in denial, will blame and attack others.

- Psychology: Delivering “just” punishment.

Rescuer:

- Statements: “I guess I’ll just be the one who has to do this.” “This is for your own good.”

- Behaviors: Focused on others, fixing problems, ignoring own needs, advice-giver.

- Internally: Driven by guilt, high anxiety, low sense of self. Feels sense of importance when someone is rescued (enter the victim). Sees themselves as a helper or caretaker.

- Psychology: The classic codependent (and enabler).

Victim:

- Statements: “No one appreciates what I do.” “Here I am, helpless, left all alone.”

- Behaviors: Makes excuses, blames others, pouts, won’t apologize, shuts down.

- Internally: Feels disappointed, believes they are not cared for, thinks they do not count, overlooked and overwhelmed.

- Psychology: Worthless and damaged; “Murphy’s law.”

Sarah continued to watch her friends get married off, one by one. She is sick and tired of being the one no one wants, the Victim. Her circle of friends after college is getting smaller by the week, and the ones she still talks to are more difficult to relate to, because they have their busy lives with their families. She meets Nate, and he loves making her feel special. She quickly thinks she’s in love. Nate feels incredible that he can help Sarah with all her problems, her Rescuer, and finds identity in this. However, when he decides to spend a weekend with the guys, Sarah objects, with Nate exploding as the Persecutor, telling her she needs to stop suffocating him, and Sarah withdraws into herself as the Victim, realizing it is her lot in life to be rejected.

In the Drama Triangle, though there is a primary role, sometimes referred to as the “starting gate,” a person will/can switch between different roles. In the diagram above, the two roles at the top are placed there because of their relative “one-up” position. But if a person functions anywhere on this triangle, they will eventually end up as the victim.

Why continue on this defective course? There are many reasons, or “pay-offs.”

- Meeting legitimate needs for love, respect, and intimacy in illegitimate ways.

- Denial- avoids painful truths and real emotions.

- Poor emotional regulation and reacting rather than being proactive.

- An identity is provided- a sense of direction can be felt when a person fills a role, even if harmful.

- Offers a sense of closeness (ever felt closer to someone you argue with vs. apathy?).

- Offers a position of power over another.

- Avoids personal responsibility.

- Inner drama is converted externally.

- Cycle of shame- feeling defeated enough that a person continues to choose defeat.

Lynne Forrest (2008)[2] poignantly observes, “Whenever we refuse to take responsibility for ourselves, we are unconsciously choosing to react as victim.” When we don’t take responsibility, we miss out on the blessings and avoid the natural consequences that help us grow up. Shielding from reality turns sanity into insanity. If you’re looking for a way to feel miserable, wait for everything outside of you to change before you can be content. However, there are ways to give up the drama.

Trading in your Role. Sorting through genuine beliefs and feelings, owning them, and pursuing solutions, options, and personal responsibility are all a part of being a healthy adult.[3] You can choose well-being, even if others don’t. Negotiating boundaries is not about controlling another person. It is about truth rather than drama. It is about respect rather than demoralization.

Empower instead of disable others- instead of making someone dependent on you or being dependent on another for salvation, a place of humility is needed. Humility generates the best self-esteem; it is seeing yourself and others with a clear, respectful lens.

- Identify and communicate in suitable ways how you truly think and feel.

- Maintain, implement and follow-through with boundaries.

- Admit you make mistakes regularly.

- Negotiate options. Often, there are many options available.

- Avoid talking down; dialogue.

- Grow in self-awareness. Seek to understand what others really think by asking them.

- Stay teachable and willing to learn.

- Realize relationships are complex- there may not be an easy answer, and your perspective is only one.

- Unify your heart and head (be not only intellectually intelligent, but emotionally intelligent).

- You can’t have it your way all the time. Learn to sacrifice.

Steve wasn’t “on his first rodeo.” As a classic Rescuer who was the oldest child and the trusted man of the house when his father abandoned the family, he learned to find value in fixing broken things. He would say yes to projects at the church, neighbors’ requests, girl scouts, 70 hr./week workloads- and then he crashed. After ending up with suicidal thoughts and deep resentment (Victim and Persecutor) that others didn’t care for him like he cared for them, it was in therapy that his counselor first introduced him to The Drama Triangle. When he realized he was creating his own chaos by living out unhealthy and, often, unseen patterns, he developed “muscles” around saying no, having limits, and allowing margin (aka, breathing room) in his life. And he finally found that he stopped attracting other women who took advantage of him- because he allowed it in the past. Now Steve is conscious that well-being requires daily work, but finds the reward of not living out of obligation and guilt, but rather choice and love.

[1] Karpman, Ph.D, Steven (1968). Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis.

[2] Forrest, Lynn (2008). The Three Faces of Victim.

[3] McGill, Ph.D, Ken (2014). “Cultivating Love.” The Karpman Triangle and The Equality /Empowerment Triangle.

Leave a Reply