OCD in context.

You may already be very familiar with references to OCD, especially in the larger culture. “I’m soooooo OCD” is a phrase, often unhelpful to true sufferers, that reflects the current sentiments of many as to what it is. Neat. Picky. High Standards. Demanding. This is NOT necessarily OCD in and of itself. If you have the real deal, know this: it’s a very challenging disorder, AND it’s highly treatable.

Though the most common obsessional concern is contamination and the most frequent compulsions involve checking and/or cleaning/washing, there is remarkable diversity in how people struggle with OCD. Any fear or discomfort a person may have can be implicated in OCD.

Common Obsessions:

Contamination

Doubt

Perfectionism

Harm to others or self

Somatic (body and health) concerns

Sexual or violent thoughts

Religious/scrupulous/existential thoughts

Common Compulsions:

Washing/cleaning

Checking

Repeating

Mental rituals (praying, counting, reviewing)

Reassurance seeking

Ordering

Avoidance (including distraction and suppression)

Asking/Confessing

Neutralizing/Suppressing

What is OCD?

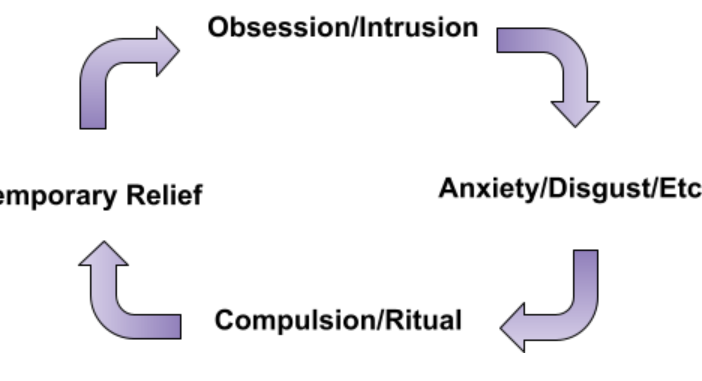

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a mental health disorder characterized in three parts. First, Obsessions are intrusive and unwanted thoughts, urges, or impulses which cause marked distress or anxiety. They are recurrent & persistent. Secondly, Compulsions, or rituals, are attempts to avoid, suppress, ignore, or neutralize such distress (whether experienced as disgust, fear, doubt, a desire for completeness, etc.). This can be either through overt behavior or thought (“mental acts”). They are aimed at minimizing or avoiding distress or anxiety. The final part is the level of impact and life disruption that is caused (DSM, 2013). Though the definition has tightened over time with more study, by and large various descriptions throughout history can be seen reflecting OCD. In fact, it was the clergy who were some of the first to catalogue obsessions and rituals (Stanford, 2021)!

Who has OCD?

About 1-2% of the population can be diagnosed with OCD, across socioeconomic, cultural, gender, religious, and other differences (Ruscio et al., 2008)- that’s over 150 million people worldwide. That’s not insignificant, especially considering that it causes some of the greatest disability in the world.

A majority of all people, with or without OCD, endorse having intrusive thoughts. Those with OCD have a brain-based disorder that repeatedly sets off their neurobiological “alarm system”, which makes it more difficult and distressing to ignore and move on from intrusive thoughts.

What Causes OCD?

The exact cause of OCD is unknown. There is a strong genetic component (it “runs in families”), being moderately inherited, with estimates ranging widely from 27% to 65% (Ruscio et al, 2008).

Neurobiological abnormalities (brain scans look different in someone with OCD) are thought to abound. Strep infection, particularly in childhood, is still being researched as an onset of severe symptoms. Stress may trigger OCD, though this is typically true with many conditions. Traumatic brain injuries (TBI), especially in childhood, increase the association. (Grados et al., 2008). Theories abound as to other causes be it environmental, post-natal, and more.

How Impactful is OCD?

OCD can be very debilitating. In its global research, the World Health Organization lists OCD with anxiety disorders as the “sixth largest contributor to non-fatal health loss” (disability) (WHO, 2017). This is considering ALL illness- ‘physical’ and ‘mental.’ Two out of three individuals with OCD report experiencing severe impairment in domains of life such as work, relationships, school, etc. (Gillihan et al., 2012).

What successful treatments exist?

The two treatments of choice are CBT, specifically utilizing Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) and SRI’s.

The efficacy of ERP is high. 80% of participating patients respond well to a trial of ERP, with an average symptom reduction of 60 – 70 % (Foa, 2010; Abramowitz & Jacoby, 2015)!

SRI’s (medication) are also beneficial, with 40-60% of patients responding with an average of 20 – 40% symptom reduction (Steketee, 2012).

There are other treatments that are used, but these two are considered the first choices.

Gap between evidence and practice.

In a survey of advanced level (Ph.D) mental health clinicians treating OCD, 26% said they seldom or never use exposure for OCD. We might expect the numbers to be even more stark for those with even less training. There is evidence to believe that only around 20% of patients will receive exposure therapy for any type of anxiety disorder/OCD (Sars et al., 2015; Goisman et al., 1993). Children with all types of anxiety disorders rarely receive exposure therapy (Whiteside et al., 2016). Many in the general public have strong negative beliefs about exposure.

Getting Started.

OCD can be overwhelming. It was thought to be untreatable as recent as a few decades ago (Lack, 2012). Incredible advances have led to extraordinarily effective treatments for most who pursue effective evidence-based treatments. Get started by going to any of the following to learn more:

- IOCDF.org

- OCDGamechangers.com

- JustinKHughes.com many posts touch on the integration of faith and OCD)

- YouTube intro “Ultimate Guide to ERP for OCD”

References

Abramowitz, J. S., & Jacoby, R. J. (2015). Obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults (pp. 22-23). Boston: Hogrefe.

Boileau B. (2011). A review of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 13(4), 401-11.

Clark, D. A., & Radomsky, A. S. (2014). Introduction: A global perspective on unwanted intrusive thoughts. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders,3(3), 265-268. doi:10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.02.001

Ellison, C., Vaaler, M., Flannelly, K., & Weaver, A. (2006). The Clergy as a Source of Mental Health Assistance: What Americans Believe. Review of Religious Research, 48(2), 190-211. Retrieved February 8, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20058132

Gillihan, S. J., Williams, M. T., Malcoun, E., Yadin, E., & Foa, E. B. (2012). Common Pitfalls in Exposure and Response Prevention (EX/RP) for OCD. Journal of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, 1(4), 251-257.

Grados, M. A., Vasa, R. A., Riddle, M. A., Slomine, B. S., Salorio, C., Christensen, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). New onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms in children and adolescents with severe traumatic brain injury. Depression and Anxiety, 25(5), 398-407. doi:10.1002/da.20398

Lack C. W. (2012). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Evidence-based treatments and future directions for research. World journal of psychiatry, 2(6), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v2.i6.86

Nestadt, G., Grados, M., & Samuels, J. F. (2010). Genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 33(1), 141-58.Ponniah et. al, 2013.

Stanford Website. Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. (n.d.). History. Retrieved February 08, 2021, from http://med.stanford.edu/ocd/treatment/history.html

Ruscio, A. M., Stein, D. J., Chiu, W. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2008). The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular psychiatry, 15(1), 53-63.

Sars, D., & van Minnen, A. (2015). On the use of exposure therapy in the treatment of anxiety disorders: a survey among cognitive behavioural therapists in the Netherlands. BMC psychology, 3(1), 26. doi:10.1186/s40359-015-0083-2

Steketee, G. (2012). The Oxford handbook of obsessive compulsive and spectrum disorders (pg. 295). New York: Oxford University Press.

Whiteside, S. P., Deacon, B. J., Benito, K., & Stewart, E. (2016). Factors associated with practitioners’ use of exposure therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of anxiety disorders, 40, 29-36.

Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

Leave a Reply