Is ERP for OCD beneficial? Don’t most people drop out? Isn’t it too intense? Don’t very few people ever have long-term success?

Confusing, So Confusing

Starting treatment for something so impairing as OCD is already a challenge. Beth* expressed typical hesitations in pursuing ERP for OCD:

- Won’t focus on something terrible result in something bad? I thought I was supposed to “think positive.”

- Does it work?

- Do I have to be doing exposure all the time?

- I do not think I can do exposure with my theme- thoughts about awful things. Is that even possible?

Furthermore, she was very confused by the seemingly different assertions made by experts and even advocates for treatment. “Most people get better with treatment.” “Half of the people who try it drop out.” “Exposure is often turned down or experiences high drop out.” “Remission is rare.” “Many find Exposure intolerable.” “Exposure is insensitive.” “Exposure and Response Prevention is the best treatment for children with OCD.” “A rare number of people experience remission of symptoms.” “ERP is very effective.” So which is it?

If you have spent any time researching, you have undoubtedly seen many claims and numbers. Confused? Honestly, me too, initially—when I heard the cacophonous roar of declarations made by varying people. Beth found quick comfort when the realities of treatment—and the converse of not getting help—were looked at holistically and realistically.

What Say You, Research?

I think every one of us, when passionate about something, can unfairly present a biased picture. This phenomenon has a name well known by therapists, sociologists, and now the business world: confirmation bias. I.e., we tend to interpret evidence in light of what we already believe. When I saw Beth suffering, I first wanted to help—and my initial urge was to “convince” her of how great treatment is.

Nevertheless, as a therapist and in life, I have learned that we all grow in different ways and at different times. I cannot beneficially force someone to put their heart into anything. I laid out the fullest picture Beth needed to know for an informed decision. That transparency goes a long way, and it honors the person who’s making the time and sacrifice of therapy.

Let’s talk nerdy and get a full picture of what’s on the table.

Treatment IS Effective—In the real world, short-term, long-term, and can lead to remission

Treatment for OCD is effective; in other words, it performs well in real-world conditions (not just in controlled studies). ERP is the second most efficacious treatment in all mental health, the most being for PTSD (Cuijpers, 2019)! On average, the benefit of therapy is almost double that of medication. I.e., you are more likely than not to succeed—and these numbers are largely for initial trials and don’t even include additional options for greater complexity. There is hope.

ERP has the second-most significant treatment effects in mental health treatment, the most is for PTSD.

There are many unfounded concerns about mental health treatment being a “soft science” or a “good guess” at best. Let’s compare apples to apples—around 50% of medical treatments have unknown effectiveness. We still don’t know how many treatments work, such as acetaminophen for pain and penicillin for infections!

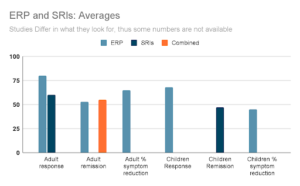

Efficacy is the ability to provide a beneficial result in research circumstances (controlled), and outcomes measure the results of interventions. The results are often reflected in a range of non-standardized wording, fluctuating between response (full or partial symptom or suffering alleviation) to remission (subclinical) or recovery (a broad, non-standardized term reflecting significant change and growth). That being said, there are some solid numbers to put forth; here is a quick summary with a table below to illustrate:

Table 1.1 Recovery from OCD- Response, Remission, and Recovery

Here’s the bulleted summary:

- Adults

- Up to 80% of those who complete ERP experience an average symptom reduction of 60-70 % (Foa, 2010; Abramowitz & Jacoby, 2015), and 53% will experience long-term remission—i.e., being subclinical (Sharma et al., 2014)—though the number ranges from 32-70% when examined up to five years out (Burchi et al., 2018). With SRI medication, around 60% of adults achieve a significant response (Hollander et al., 2003).

- Children

- They greatly benefit from ERP, but slightly less than adults, with 68% experiencing a significant response to ERP. Nearly half on medication experience remission (McGuire et al., 2015).

Technically, Adding Medication to Therapy Does Not Boost the Effectiveness

Adding medication to therapy doesn’t seem to increase the overall effectiveness in studies, which is curious, but that is not to say not to do both (many find it helpful). You don’t have to add medication to therapy automatically (Foa, 2010).

Relapse and Dropout

Relapse (returning to full criteria of OCD with impairment) does occur, ranging wildly from 30-68%, depending on the study. Relapse is not a failure; it is essential to address it for long-term benefit. Because OCD is chronic or episodic, it must be managed as such.

Full remission (minimal symptoms and no impairment for eight weeks) is associated with a much lower risk of relapse. In other words, treatment will be more “durable” and lasting if taken to completion (Burchi et al., 2018; Eisen et al., 2013).

The dropout rate is not any higher than any other CBT treatment, with 14.7% dropping out after starting and another four percent refusing treatment upfront (Ong et Al. 2016). In fact, for CBT in general, 26.2% of patients drop out (Fernandez et al., 2018). Can you believe that—treatment that exposes someone to what they fear—and yet the drop-out rate is less than CBT as a whole?!

The dropout rate for ERP is less than CBT as a whole!

Improvement Rates—From Rapid to Long-Term

Each study above has its own differences, but often a clinical trial of ERP is considered 16-20 exposure sessions of 90 minutes, 2-3 times per week outpatient in many studies. Medications also differ but often require 12 weeks, with four to six being at maximum tolerable dosing (Janardhan Reddy et al., 2017). Medications are recommended to be continued for one to two years after remission (APA, 2007). Typically, a starting point for treatment will be a minimum of three months.

Rapid improvement is possible for OCD, though it is not a fit for everyone. A more intensive regimen can address this condition quicker in some cases. One study saw an improvement rate of 62% in only three weeks (Lindsay et al., 1997). The Bergen 4-day treatment (B4DT) model has published stunning results, equally effective in children and adults, regardless of severity: 90% improved, 68% reached full remission at 12-month follow-up, and after four years, 69% were considered recovered (Hansen et al., 2018a and b).

To be clear, the administration of these intensive methods is not yet an established protocol for all people (i.e., not recommended for all, yet they all still utilize the critical elements of the first-line recommendations). These offer some great insights into the opportunity for rapid improvement and hope to develop alternative approaches. As one of my research friends recently said, “Find a cure or die trying!” Haha, I like that. Yes, we’re nerds.

Where Are You? Take a Step!

The simple conclusion is that treatment helps a LOT, especially ERP, but it is not a cure. Most people do not drop out as a whole, and certainly not any more than any other therapy. There is still room for growth and finding support for gaps.

No treatment approach works 100% for all people, and for those who haven’t gotten the help they wish for, additional options exist besides SRI medications and ERP therapy. On the fence? I hope you’ll at least take one small, tangible step. Maybe it’s reading. Possibly, it could be a consultation with an expert. A gentle reminder: you are not locked into anything by exploring! Ask questions, “grill” us professionals with questions—we’re trained for it and are here for your best benefit. And on that note, I say, Blessings!

Interested in being on the cutting edge? Get updates and free ebooks from my newsletter! For those interested in my forthcoming book on OCD recovery for Christians, follow the “Christian” list.

*The key examples in stories I use are real, though I change the names and use composites of multiple people I have talked with and/or treated in a way that would make it impossible to identify them.

Bibliography

Abramowitz, J. S., & Jacoby, R. J. (2015). Obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults (pp. 22-23). Boston: Hogrefe.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with the obsessive compulsive disorder. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2007.

Burchi, E., Hollander, E., & Pallanti, S. (2018). From Treatment Response to Recovery: A Realistic Goal in OCD. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 21(11), 1007–1013. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyy079

Cuijpers P. (2019). Targets and outcomes of psychotherapies for mental disorders: an overview. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(3), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20661

Eisen, J. L., Sibrava, N. J., Boisseau, C. L., Mancebo, M. C., Stout, R. L., Pinto, A., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2013). Five-year course of obsessive-compulsive disorder: predictors of remission and relapse. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 74(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m07657

Fernandez, E., Salem, D., Swift, J. K., & Ramtahal, N. (2015). Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: Magnitude, timing, and moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1108–1122. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000044

Foa E. B. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 12(2), 199–207.

Foa E. B. (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 12(2), 199–207.

Hansen, B., Hagen, K., Öst, L.-G., Solem, S., & Kvale, G. (2018a). The Bergen 4-day OCD treatment delivered in a group setting: 12-month follow-up. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00639

Hansen, B., Kvale, G., Hagen, K., Havnen, A., & Öst, L.-G. (2018b). The Bergen 4-day treatment for OCD: Four years follow-up of concentrated ERP in a clinical mental health setting. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(2), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1478447

Hollander, E., Friedberg, J., Wasserman, S., Allen, A., Birnbaum, M., & Koran, L. M. (2003). Venlafaxine in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 64(5), 546–550. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v64n0508

Howick, J., Koletsi, D., Pandis, N., Fleming, P. S., Loef, M., Walach, H., Schmidt, S., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2020). The quality of evidence for medical interventions does not improve or worsen: a metaepidemiological study of Cochrane reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 126, 154–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.08.005

Lindsay, M., Crino, R., & Andrews, G. (1997). Controlled trial of exposure and response prevention in obsessive-compulsive disorder. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science, 171, 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.171.2.135

McGuire, J. F., Piacentini, J., Lewin, A. B., Brennan, E. A., Murphy, T. K., & Storch, E. A. (2015). A META-ANALYSIS OF COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY AND MEDICATION FOR CHILD OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER: MODERATORS OF TREATMENT EFFICACY, RESPONSE, AND REMISSION. Depression and anxiety, 32(8), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22389

Ong, C. W., Clyde, J. W., Bluett, E. J., Levin, M. E., & Twohig, M. P. (2016). Dropout rates in exposure with response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: What do the data really say?. Journal of anxiety disorders, 40, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.03.006

Sharma, E., Thennarasu, K., & Reddy, Y. C. (2014). Long-term outcome of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(09), 1019–1027. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.13r08849

Smith QW, Street RL, Volk RJ, Fordis M. Differing Levels of Clinical Evidence: Exploring Communication Challenges in Shared Decision Making. Medical Care Research and Review. 2013;70(1_suppl):3S-13S. doi:10.1177/1077558712468491

Leave a Reply